Remembering Rita, “The Other” Hurricane

By Autumn of 2005 the subtle suggestions of a changing season were being felt, not in a big way like in places where the leaves turn orange but in subtle ways: the cane fields being harvested; an occasional chill; embers from a pig roasting; and on the radio a crowd cheering as the LSU band fast-steps on the field while playing a frenetic version of “Hold That Tiger.”

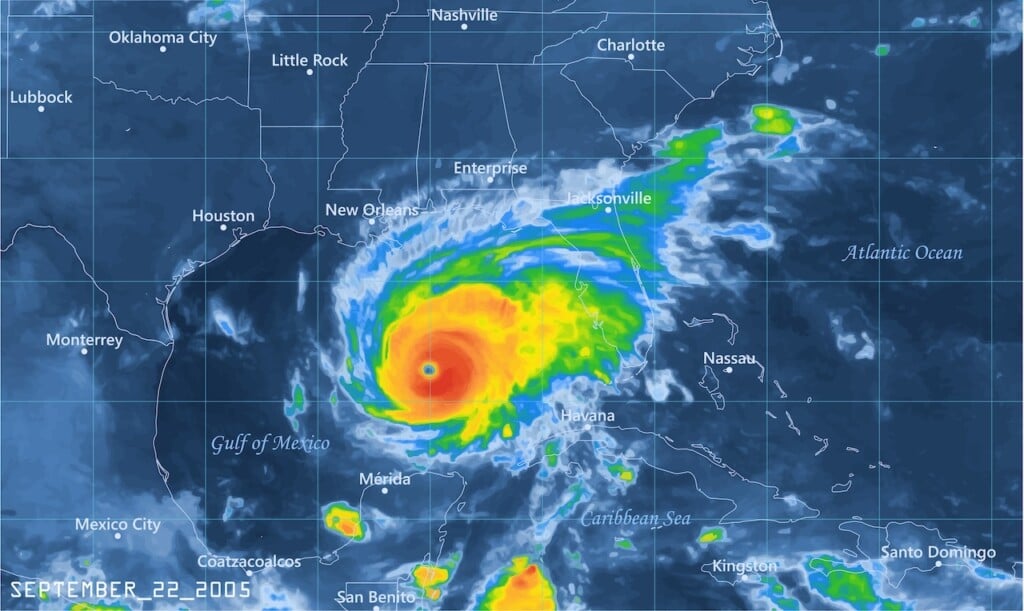

Autumn in Louisiana can be a sensory time, but in 2005 the senses were strained. By the end of August most of the state, particularly the New Orleans area, and then across the bayou country toward Texas and even turning up toward Shreveport, had suffered through two major hurricanes. First there was Katrina, which made landfall Aug. 29. It would be the first and most remembered storm, but within less than a month there came another one. It didn’t seem fair because much of the state had just been leveled by Katrina. The new beast (which entered the state at Cameron Parish Sept. 24) was called “Rita.” In the introduction to his book “Hell or High Water: How Cajun Fortitude Withstood Hurricanes Rita and Ike” author Ron Thibodeaux wrote that, “Rita clobbered communities across the entire 250-mile coastal foundation of Acadiana, America’s one-of-a-kind Cajun country. From one end of the Louisiana coast to another, towns were flooded, populations were left homeless and without public services, and communities were all but wiped off the map.”

Referring to Rita as “the other Louisiana disaster of 2005” Thibodeaux continued: As soon as Rita trailed off the National Weather Service radar, it also disappeared from the American consciousness. While New Orleans remained headline news, the communities hit so hard by Rita were all but forgotten and left to fend for themselves.

Even those parts of the state not directly hit by the hurricanes were affected by them at the very least by trying to provide for, and in some cases, trying to tolerate, the rush of evacuees.

Katrina also had a psychological effect on the anxiety that Rita would stir. With TV images still fresh from the evacuation of the New Orleans area only a few weeks earlier, residents of coastal Louisiana and East Texas, as far as Houston wanted to avoid similar experiences and jammed the highways heading for somewhere else. Top winds reached 180 mph. Between Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi and Florida, there were 120 related deaths, some due to the heat and exhaustion from evacuating. Louisiana only had one fatality. (The storm’s worst incident happened near Dallas where a bus carrying evacuees from a nursing home caught fire. There were 23 fatalities.)

Everyone had plenty to worry about, especially families with school age kids. All of this disturbance was happening at the same time of the year when schools were just opening. That would affect decisions of where to evacuate to, especially not knowing the condition of the schools. At a bed and breakfast in Mansura where I initially stayed, a kid was shipped to California where an aunt had arranged for special entry into a school there. There were tears on the morning when the mom left with her son to fly him to another land where had never been. Most area schools were generous at taking in, even if it would be for a short while, evacuee kids. In New Orleans, it had been reported that the city would be under water for at least six months. That would prove not to be the case, but it caused a lot of long-term worry for many parents.

Everyone would have Katrina stories to tell and there are millions of them. Mine include early Sunday evenings in the lobby of the Avoyelles Parish Paragon casino. There was usually a crowd there, not so much for gambling but for WI-FI. The technology was just becoming available, and the hotel was one of the few places to take advantage of it. Sundays always seemed like a good time to reach folks. WI-FI worked in wondrous ways. Sometimes in the lobby, we met folks from home who also were clicking their laptops.

My favorite Katrina story was the mystery of rhythm- and- blues man Fats Domino who would have been much better off had he lived on his song title, “Blue Berry Hill” rather than below sea level. His home was in eastern New Orleans, an area that was hit hard by flooding when the levees broke.

There were reports that he was missing. And then there was a news picture of the septuagenarian boarding a rescue boat. Ultimately, he wound up in a crowded apartment in Baton Rouse where the tenant happened to have connections with Domino’s family. Fats and other family members were found and taken to the apartment where he reportedly slept on the sofa.

Oh, and the tenant whose apartment Domino stayed in was named JaMarcus Russell. Being a R&B star is highly prestigious; but even more prestigious, especially in Baton Rouge, was Russell’s title — the starting Quarterback for LSU. The fact of Fats being rescued by the LSU quarterback goes beyond the expected boundaries of fiction — but it is true.

In 2007, Russell was the first-round draft choice of the Oakland Raiders launching a brief career in the pros. Fats would return to New Orleans where the reclusive star would perhaps spend time listening to his hits.

One of his top sellers was called “Walking to New Orleans.”

I’ve got no time for talkin’

I’ve got to keep on walkin’

New Orleans is my home

That’s the reason while I’m gone

Yes, I’m walkin’ to New Orleans

Fats seemed determined. Maybe Russell could have provided a ride.