20 Years Ago – The First Days of Katrina

On the evening of August 26, 2005, I was in the owner’s suite at the Superdome. (I had gained entry not because of rank but because of luck and knowing one of the hosts.) The event was a mere pre-season game, against the Baltimore Ravens.

There was a nice buffet and a bar, most of all there was the suite, which owner Tom Benson’s wife, Gayle, an interior designer by trade, had skillfully redecorated.

Sitting alone on a stool in a corner watching the game was Benson. He did not seem very happy; perhaps because the Saints were not playing well but more so because he had heard the news that was starting to worry everyone: the tropical system in the gulf that for days, we had heard, was going to move up the Florida panhandle had changed direction. According to the National Weather Service, it was now moving toward the Mississippi/Alabama coast. Later that day, the system, to be known as Katrina, was upgraded to a Tropical Storm. Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco had declared a state of emergency.

As worrisome as the evening was getting to be, Benson would have much more ahead to worry about. Fitting the mood of what would be ahead, the Saints lost to the Ravens that night 21-6. No one could imagine that the team would not return to the dome that season, not until September 25, 2006 — more than a year later.

Saturday August 27

At 3 p.m., New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin declared a state of emergency for the city. That evening Nagin went around to all the television news stations, which by then were doing continuous coverage of the approaching storm. At each, he addressed the citizens urging them to prepare for a voluntary evacuation. (I have thought about that evening many times. Nagin would have legal problems later in his career but that evening he was heroic as he spread an alarming message. Could there be a worse moment in the career of a mayor than having to urge his constituents to leave town — soon? “No weapons, no large items, and bring small quantities of food for three or four days, to be safe,” he said.

Sunday, August 28

No longer was it voluntary. At a 9 a.m. press conference Nagin declared, “a mandatory evacuation order is hereby called for all of the parish of Orleans.”

He added, “We are facing a storm most of us have long feared.”

That morning, I received several phone calls from friends all discussing evacuation option. I was especially touched by the words of one friend, saying “I wish I could pay someone to tell me what to do.”

By late afternoon, we, including an uncle whose physical state was such that we knew he would not survive an emergency shelter, were on I-10 headed west toward Central Louisiana and family in Marksville. Near LaPlace, the traffic was stalled. I remember stepping out of the car and looking back toward New Orleans. The afternoon sky was an ominous black like a creature rising from the sea and clutching the city. This was the first moment I felt fear. What if the traffic would not move again and thousands of vehicles would be stuck on the interstate because of that big ugly creature?

Fortunately, movement, though slow, began as the police opened traffic lanes that had been closed for construction near the Bluebonnet exit in Baton Rouge. For nearly two hours, all of South Louisiana seemed to be squeezed into one lane. We must have arrived in Marksville around 10 p.m. Along the way, there had been lines at gas stations and truck stops. I-10 would become a major artery in the state’s survival for the next few months, though there would be days when there was no entry allowed into New Orleans.

Monday, August 29

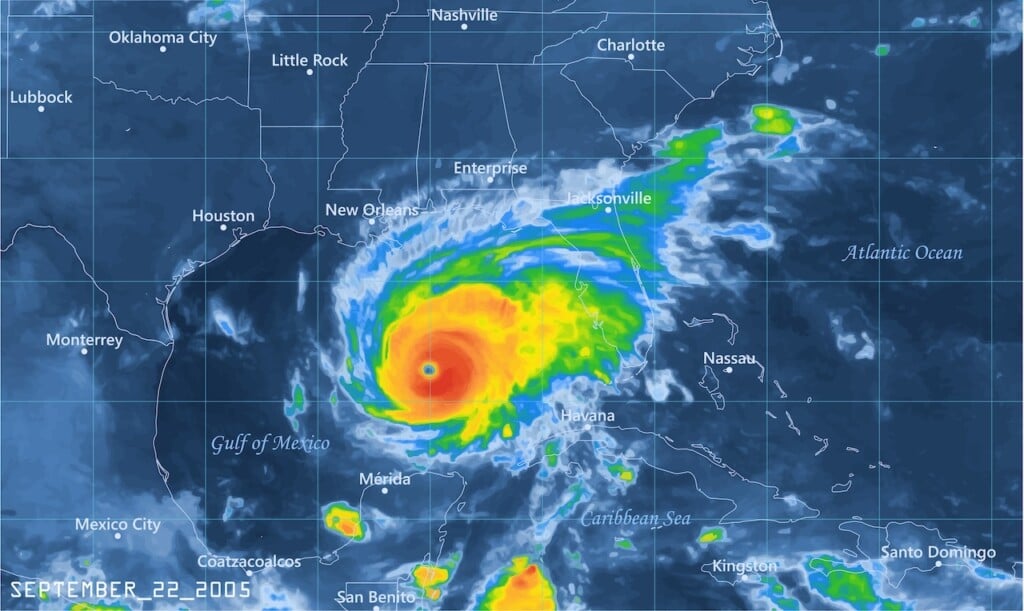

A satellite image of a swirling storm was on the front page of the Alexandria Town Talk that morning. The headline was horrifying: “This is the Big One.” For years, scientists had been talking about the “big one,” a hypothetical full intensity storm that would approach New Orleans straight up the river, pushing high waters into the connecting lakes and streams forcing their levees to break and causing major flooding. The big one indeed.

We were in Marksville. Relying on radio and TV coverage from New Orleans for most of the day, it looked like the storm was not going to be as bad as feared; trees were knocked down and power was out. The most visual damage was to the historic Southern Yacht Club. The wooden building had caught fire and would be totally destroyed, but the surrounding area had survived. I remember thinking that we would be heading back home by Wednesday.

Then that night while listening to radio station WWL, whose 50,000 watts of power make it the voice for emergency situations, an announcement was made by News Director Dave Cohen. I remember the moment as he reported that the city’s levees have been breached and there was uncontained flooding throughout most of the city. From that moment, our lives changed.

When I first returned to my home several weeks later, I saw a neighbor walking down the street. “Listen,” he said. “What do you hear?” We both agreed — “nothing.” There were no birds around just total silence — the non-sound of a lifeless neighborhood.

Everyone would have Katrina stories, millions of them. The one I remember most was a brief conversation. For the first few days after the storm, we stayed at a Bed and Breakfast in Mansura. Among the other refugees were two families who lived upriver from New Orleans. The two moms were sisters. One morning we were sitting in the kitchen looking at the horrifying TV coverage of submerged New Orleans. “Every time I see that,” one sister told the other, “I want to cry.”

“I do too,” the other answered, “but I am afraid if I start, I will never stop.”

That’s what life was like as August 2005 slipped into September. The levees had failed to hold back the water; now we were trying to hold back the tears.