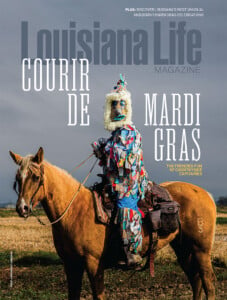

A Look Inside Louisiana’s Courir de Mardi Gras

The three capitaines are busy working on their whips. Astride horses, they wear jeans, boots, button-down shirts, black hats. From their shoulders hang lustrous capes. They flutter, purple, green and gold in the February

chill. A quick shriek like scratching against the dawn and two men sauntering past in quilted costumes turn as a capitaine tears duct tape with his teeth.

Linger beside them for a moment, those two costumed men. In local parlance, they are the Mardi Gras, for here, the name of the reveler replaces that of the revelry. Watch with them as the capitaine molds tape around the whip, his face fixed in mischievous grin. He works like a surgeon layering strips of plaster onto a cast while each of the other men braids two whips into one, doubling their size to three inches in diameter, four.

Another shriek from beside them and the capitaine resumes his molding and shaping. Once satisfied that the whip is nearly equal parts gray and brown, he offers the tape to the others.

Various courirs, or runs, take place in Southwest Louisiana during carnival season. They typically occur on weekends and finish on Mardi Gras day.

“Try some of that,” he says. “It hurts more this way.”

Admiring this new creation, they break into laughter. Then another sound reaches from behind. Horse hooves shovel-slush over loose gravel and one by one, the capitaines turn to greet their reflection, an approaching rider in jeans and boots and button-down shirt. This one presses his palm atop the black hat to prevent it from sailing away. Pausing beside the others, he examines the Frankensteined whip.

“You don’t want to be on the other side of that,” he says.

And again it comes, a chorus of laughter, the lifeblood of Carnival.

If there’s one certainty on a day when anything can happen, it’s this: Set out into the countryside with these capitaines and Mardi Gras and you will eventually become the bull’s-eye for of one of those whips. You may even commit acts that warrant it. Beside a crawfish pond, say, you will feel a sudden urge to wade in and pilfer a trap simply because it is there and you are here, and this is the day of days.

“Mardi Gras, put that trap back,” a capitaine will say, and the only question then is how far you’re willing to push against the fabric of order.

All the world may be a stage, but even Shakespeare at his most imaginative couldn’t have envisioned an annual ritual such as this. If he’d had the good fortune to participate in Louisiana’s Courir de Mardi Gras, he might have composed sonnets about how everything on this day becomes a potential prop, the entire procession an epic that every participant composes and performs with each step. Even if you’ve run the route a dozen years straight, each time is always the first time.

So maybe it’s not the trap. Maybe midway through the journey, you find yourself sneaking behind a capitaine to pluck that black hat from his head. In the world of the Courir, such a violation provides a glimpse into immortality, and at some point, you decide it would be wrong if you didn’t try.

In its costumes, capuchons, clowning, begging, gender and role reversal and mock flagellation, the courir resembles festivals from medieval Europe.

Now you’ve got that hat in hand and you didn’t think you could run this fast, but since this isn’t the real world, anything is possible. Your feet float across a soggy field, and then you pirouette to avoid colliding into a Mardi Gras who’s waterskiing behind a horse, and in that moment, you hear them coming for you — two capitaines, one sans pseudo Stetson — their whips cutting through the air. Horse hooves slap against the waterlogged earth, but that sound seems muffled compared to the samba-blast of your heart. And you run, clutching the hat to your chest, more certain than ever that life is short and Carnival is long.

The first whip misses. It’s merely a rumor, hot breath teasing flesh, but the second one connects. You feel the pop, also the one that comes a moment later, nothing more than temporary tattoos, and as you toss the hat and continue your mad dash across that field, all you can do is laugh.

Welcome to the Courir — French for run. This is the carnivalesque in its purest sense. It’s what Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin had in mind when he deemed Carnival “the world inside out,” a parallel realm whose true nature “frees human consciousness, thought and imagination for new potentialities.”

On this single day of the year, you can be anyone, do anything. Unlike the unmasked capitaines, the Mardi Gras move anonymously through the countryside, unknown — at least that’s the idea — among those who congregate on the sides of roads and at homestands to bathe in the performance of their motley procession. It begins shortly after dawn and winds its way deep into the afternoon, all the singing and dancing, the begging for ingredients to make a gumbo for everyone to enjoy at the end of the run, the dozen miles of traversing thin and busted country roads on foot, horseback and by wagon — but first, they will stand atop horses and chase chickens until the capitaines lead them back onto the road, headed for the next stop.

Once there, the band will strike up a song while the Mardi Gras slither across the lawn and shriek like swamp creatures, begging for money and ingredients for that communal gumbo, chiefly a prized chicken, and soon a capitaine will give the order: “Mardi Gras, y’all dance with the women.” And they dance with the women. They dance with the men. They dance with the children, and they dance with one another.

At the outset, you should know a few things about what you’re getting into if you choose to don a mask and capuchon, the conical hat that once mocked the nobility in medieval Europe, where this tradition started and continues its mocking each year throughout various communities in Southwest Louisiana. Since you’re going to maraud and plunder your way through the countryside, tight roping the gray area of the law at times just to see if those capitaines can control chaos, it only seems fair, at the outset, to provide a few facts. This isn’t a parade on St. Charles Avenue. You won’t find any beads or doubloons here. No bejeweled men or women sit atop ornate floats to mime the stilted coronation wave. No. You’re going to have to slip into a new skin to participate in this one. You’re going to need a new imagination.

Gus Gravot, who works with the U.S. State Department in the real world and often runs as a capitaine in the dreamscape of the Courir, explains it this way: “In New Orleans, you go to the procession. Here, the procession comes to you.” When his job permits, Gravot returns home and, wearing his hat and cape, mounts a horse with his corne de vache, blowing into that horn to provide the traditional signal that the Courir has commenced. “In New Orleans, the procession gives to you,” he says. “Here, you give to the procession.”

But to be in this procession also means to give — to the community and to one another. By the end of the run, everyone takes part. In the spirit of anything goes, you shouldn’t worry about appearing foolish when, in local parlance, acting the fool resides near the top of the day’s unspoken commandments. There are no boundaries here, no divisions between reveler and spectator.

Some runs are for men only, others for women alone. A few welcome any adult, while some allow only children under age 16.

So this is where you’ve found yourself, a traditional Courir in Southwest Louisiana. Various runs take place here throughout Carnival season. Most are male only. Some are for women alone, others mixed, a few for those under age 16. Today, you’re among Les Malfecteurs — the Outlaws — a male-only run that started in 2021 after organizers of the Church Point Courir de Mardi Gras cancelled their event due to COVID. Unable to fathom a year without a run, Les Malfecteurs organized a one-off, thinking they would return to the larger, less traditional Church Point Courir once it resumed. But during that first run, they sensed the birth of a ritual. And why stop a good thing? Now, a group of about six dozen men — capitaines, musicians and Mardi Gras — daydream their way through the calendar, anticipating the morning they find themselves in the parking lot of a ranch four miles outside Church Point, making their final preparations to set out.

It’s still too early for those capitaines to get philosophical about much other than inflicting pain, but later, farther down the road, when they start ruminating about what all this means and how the day binds them to ancestors who once wore similar capes and hats and ran some of these same roads, one of them might provide a Courir mantra: “If we threw this party anywhere else, we would all get arrested.”

Distances vary for each run. Some traverse more than a dozen miles. Capitaines typically ride horseback. The revelers, known as Mardi Gras, either ride horseback, walk, or sit in wagons. At each stop, the band plays and sings for homeowners and the community while the Mardi Gras dance, perform, and beg for ingredients to make a communal gumbo. The ultimate prize is a chicken, which the Mardi Gras chase.

And there’s a glimmer in his eye, just a flicker, but enough to make you understand that he’s considered what it would mean to take this party on the road. Set out with them from Church Point, Mermentau Cove, Elton, Lejeune Cove or Mamou. See what happens when the rest of the country—even those other parts of Louisiana where residents remain unaware that one of the world’s most authentic Carnival traditions takes place in their own back yard — finally witness what it means to truly pass a good time.

First, you need a priest.

Here he comes in cassock and collar. He makes his way toward the wagon, and one by one, the Mardi Gras part. Silence settles over the morning while the priest asks God for a safe run. Since it’s your first time, you will have those words in mind when, hours later, the Mardi Gras identify you as a “fish,” and a scrum of men carries you toward your baptism. By then, you will have begged and danced and thieved your way across nearly a dozen miles of countryside. You’ve been soaked for hours, but staying safe and dry is for the other days of the year and after all, it is written somewhere, or maybe not: every novice must swim. As you plunge into the murky water, you will remember the phone in your pocket. Resurfacing, gasping for breath, you hear the musicians’ instruments settle over the tableau: a flurry of dancing Mardi Gras. And for a moment, you wonder why you ever worried about something as ephemeral as a gadget.

Drenched, shivering, you thank the homeowners and with the procession, move to the next stop. You are exalted, exhausted, but the time for rest and repenting will come later, when on Ash Wednesday the priest presses a cross upon your forehead. Now is the hour to hang upside down from limbs slimmer than your forearm, to ascend houses and barns and basketball goals and drum your palms against rusted roofs and fiberglass, to pluck another of those black hats from a capitaine’s head before it’s too late.

So here you are, walking among the column of Mardi Gras, each of you conspiring to tune the world to the frequency of the Courir, this opera of mayhem in which song and laughter fall like hard rain across the Louisiana landscape.